New Delhi: Aruna Roy's two cellphones were ringing before breakfast on Tuesday as she braced for another day in the media storm of the Anna Hazare anticorruption movement. Ms. Roy, a pillar of India's civil society who has fought for greater government accountability, has been appearing on television to talk about Mr. Hazare's populist campaign, which includes his current hunger strike. She might seem a natural ally.

She is not.

Ms. Roy opposes the negotiating stance taken by Mr. Hazare and his advisers, and opposes their solution to official corruption. Nor is she alone. Much of India's intelligentsia, if sympathetic to fighting corruption, has greeted the Hazare movement with unease or outright hostility, with one critic describing some elements of the flag-waving, middle-class supporters as an Indian incarnation of the Tea Party.

The strongest criticism is still directed at India's government leaders, who are blamed for mishandling the crisis and for failing to combat corruption as public disgust deepened in recent years. Yet the strident tone taken by Mr. Hazare and his advisers, their seeming unwillingness to consider other perspectives and their effort to bypass parliamentary processes has brought a wide range of criticism, even from some otherwise natural allies.

By and large, there is a great deal of concern with the movement and the nature of the movement," said Zoya Hasan, a political scientist at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. "Not with the issue. People agree something has to be done and the government hasn't done enough."

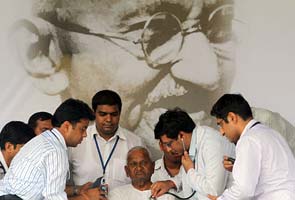

The immediate question is how to defuse the crisis as Mr. Hazare on Tuesday reached the eighth day of his hunger strike at Ramlila Maidan, the public ground in New Delhi. His Gandhian fasting campaign has attracted huge crowds at peaceful rallies or marches across India in a movement that has startled the political establishment with its size and potency.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on Tuesday sent a private letter to Mr. Hazare that apparently helped clear the way for direct talks that quickly started between a top government minister and the Hazare camp. Hours later, Mr. Hazare announced to supporters at Ramlila Maidan that he had rejected advice from doctors to begin taking a glucose drip to prevent kidney deterioration.

"My conscience told me, 'Why are you scared of dying?' " he said in remarks carried on national television. "If you say that you can die for the nation, then why are you scared?"

Beneath the drama, the impasse is actually a legal dispute over whose legislation should be the basis for creating a new, independent anticorruption agency, known as the Lokpal. Mr. Hazare's team has disparaged a government bill pending in Parliament as deliberately ineffective and intended to protect public officials more than scrutinize them. Many other analysts agree.

Yet many of those same analysts are disturbed by the alternative put forward by Mr. Hazare's team: an independent agency with sweeping powers and its own vast, nationwide bureaucracy that critics say could exist outside the usual checks of India's democratic systems.

Arundhati Roy, the leftist writer and outspoken government critic, writing in The Hindu, an English-language newspaper, assailed the Hazare bill as "a draconian anticorruption law, in which a panel of carefully chosen people will administer a giant bureaucracy, with thousands of employees, with the power to police the prime minister, the judiciary, members of Parliament, and all the bureaucracy, down to the lowest government official."

From a very different place in the political spectrum, Manish Sabharwal, a corporate leader, argued that the Hazare team's emphasis on creating a super-policing agency is too simplistic and ignores the multitude of steps needed, from reforming election laws to increasing transparency in government contracting.

Perhaps the most widespread criticism, strongly denied by the Hazare team, is that their tactics are undemocratic and represent an attack on India's lawmaking processes. In particular, critics have pointed to the claim by the Hazare group that their legislation represents the people's will and should replace the government bill in Parliament. In recent days, they have argued that trying to change the government bill as part of the parliamentary process is futile, and Mr. Hazare has vowed to continue his fast unless his bill is passed in Parliament by Aug. 30.

For Ms. Roy, the civil society leader, criticizing the Hazare proposal means arguing with former allies. She was a leader in the civil society campaign that established India's Right to Information law, a landmark piece of legislation that allows citizens to demand government information. Two of her allies are now advisers to Mr. Hazare on the Lokpal issue.

Today, Ms. Roy and others are proposing a third option that would create a Lokpal with multiple agencies rather than the all-powerful body envisioned by the Hazare team. Herself a Gandhian, Ms. Roy also questioned the Gandhian credentials of the Hazare movement. "I would say the tactics are Gandhian but the spirit is not," she said.

So far, the huge crowds turning out for Mr. Hazare have been remarkably well behaved and nonviolent, but some have urged the government to act quickly, cautioning that inaction could cause the situation to spin out of control. Late Tuesday, Mr. Hazare's advisers said talks with the government side had been constructive, while government leaders announced they would call a meeting of leaders from all political parties on Wednesday to discuss the situation.

As he spoke to the crowd on Tuesday, Mr. Hazare implored his supporters to continue to refrain from violence. But he also asked that they block the gate if anyone from the government comes to take him to a hospital.

"I am not scared of dying," he said. "Even if I die, I have created lots of Annas to carry on the fight."

She is not.

Ms. Roy opposes the negotiating stance taken by Mr. Hazare and his advisers, and opposes their solution to official corruption. Nor is she alone. Much of India's intelligentsia, if sympathetic to fighting corruption, has greeted the Hazare movement with unease or outright hostility, with one critic describing some elements of the flag-waving, middle-class supporters as an Indian incarnation of the Tea Party.

The strongest criticism is still directed at India's government leaders, who are blamed for mishandling the crisis and for failing to combat corruption as public disgust deepened in recent years. Yet the strident tone taken by Mr. Hazare and his advisers, their seeming unwillingness to consider other perspectives and their effort to bypass parliamentary processes has brought a wide range of criticism, even from some otherwise natural allies.

By and large, there is a great deal of concern with the movement and the nature of the movement," said Zoya Hasan, a political scientist at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. "Not with the issue. People agree something has to be done and the government hasn't done enough."

The immediate question is how to defuse the crisis as Mr. Hazare on Tuesday reached the eighth day of his hunger strike at Ramlila Maidan, the public ground in New Delhi. His Gandhian fasting campaign has attracted huge crowds at peaceful rallies or marches across India in a movement that has startled the political establishment with its size and potency.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on Tuesday sent a private letter to Mr. Hazare that apparently helped clear the way for direct talks that quickly started between a top government minister and the Hazare camp. Hours later, Mr. Hazare announced to supporters at Ramlila Maidan that he had rejected advice from doctors to begin taking a glucose drip to prevent kidney deterioration.

"My conscience told me, 'Why are you scared of dying?' " he said in remarks carried on national television. "If you say that you can die for the nation, then why are you scared?"

Beneath the drama, the impasse is actually a legal dispute over whose legislation should be the basis for creating a new, independent anticorruption agency, known as the Lokpal. Mr. Hazare's team has disparaged a government bill pending in Parliament as deliberately ineffective and intended to protect public officials more than scrutinize them. Many other analysts agree.

Yet many of those same analysts are disturbed by the alternative put forward by Mr. Hazare's team: an independent agency with sweeping powers and its own vast, nationwide bureaucracy that critics say could exist outside the usual checks of India's democratic systems.

Arundhati Roy, the leftist writer and outspoken government critic, writing in The Hindu, an English-language newspaper, assailed the Hazare bill as "a draconian anticorruption law, in which a panel of carefully chosen people will administer a giant bureaucracy, with thousands of employees, with the power to police the prime minister, the judiciary, members of Parliament, and all the bureaucracy, down to the lowest government official."

From a very different place in the political spectrum, Manish Sabharwal, a corporate leader, argued that the Hazare team's emphasis on creating a super-policing agency is too simplistic and ignores the multitude of steps needed, from reforming election laws to increasing transparency in government contracting.

Perhaps the most widespread criticism, strongly denied by the Hazare team, is that their tactics are undemocratic and represent an attack on India's lawmaking processes. In particular, critics have pointed to the claim by the Hazare group that their legislation represents the people's will and should replace the government bill in Parliament. In recent days, they have argued that trying to change the government bill as part of the parliamentary process is futile, and Mr. Hazare has vowed to continue his fast unless his bill is passed in Parliament by Aug. 30.

For Ms. Roy, the civil society leader, criticizing the Hazare proposal means arguing with former allies. She was a leader in the civil society campaign that established India's Right to Information law, a landmark piece of legislation that allows citizens to demand government information. Two of her allies are now advisers to Mr. Hazare on the Lokpal issue.

Today, Ms. Roy and others are proposing a third option that would create a Lokpal with multiple agencies rather than the all-powerful body envisioned by the Hazare team. Herself a Gandhian, Ms. Roy also questioned the Gandhian credentials of the Hazare movement. "I would say the tactics are Gandhian but the spirit is not," she said.

So far, the huge crowds turning out for Mr. Hazare have been remarkably well behaved and nonviolent, but some have urged the government to act quickly, cautioning that inaction could cause the situation to spin out of control. Late Tuesday, Mr. Hazare's advisers said talks with the government side had been constructive, while government leaders announced they would call a meeting of leaders from all political parties on Wednesday to discuss the situation.

As he spoke to the crowd on Tuesday, Mr. Hazare implored his supporters to continue to refrain from violence. But he also asked that they block the gate if anyone from the government comes to take him to a hospital.

"I am not scared of dying," he said. "Even if I die, I have created lots of Annas to carry on the fight."

No comments:

Post a Comment