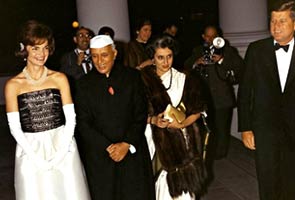

Jacqueline Kennedy, Prime Minister Jawaharlal

Nehru, Indira Gandhi and President John F.

Kennedy arrive at the White House for a private

dinner in November 1961.

Nehru, Indira Gandhi and President John F.

Kennedy arrive at the White House for a private

dinner in November 1961.

New York: In the tempestuous latter half of August - marked, in India, by a prominent activist's public fast, pop-up protests, debates about corruption, and even debates about the debates about corruption - the Congress party seemed to flounder like a dinghy in a maelstrom. Perhaps it was because no one was at the tiller. Earlier in the month, a spokesman had announced that Sonia Gandhi, the Congress president, had left the country for three weeks for surgery, and that the party would, in her absence, be run by a four-man committee.

Then even that trickle dried up; the party released no official word on what she was being treated for, where she was being treated, or when precisely she would return. When presented with rumors - of cancer, of a visit to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, of an Indian-origin oncologist being mysteriously called away from holiday - the party replied with grim silence. (She's back now - or so we were told, in an equally laconic vein.)

In this, Sonia Gandhi appeared to be following in an established tradition, by which Indian political leaders guard news of their health as if it were a state secret. Not for them the publicly fought battles of Rudy Giuliani against his prostate cancer, of Dick Cheney against his troublesome heart, or of Hugo Chavez against his recent pelvic abscess. Even the example of Mahatma Gandhi - who let it all hang out, often greeting his ashram's residents with updates about his bowel movements - is an aberration in Indian politics. The health bulletins that Mr. Gandhi issued during his various imprisonments and protest fasts may have been tools of political leverage, but they were also ways to reach out to a population that loved him deeply.

Subsequent leaders have been reticent for strategic reasons. Mohammad Ali Jinnah had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in June 1946, but he kept it from public knowledge; thus, in those charged years, few knew that Mr. Jinnah had little time left to push for an independent Pakistan. He died in September 1948, a mere 13 months after the creation of Pakistan.

It was said of Jawaharlal Nehru that India's 1962 war against China - against the fraternal power in his ideal of Asianism - sickened him and hastened his demise. But even in photographs from just before the war - from September 1962, for instance, with the nuclear scientist Homi Bhabha - Mr. Nehru seems to look haggard and ill, very different from the fit, cheerful prime minister who had met Jackie and John F. Kennedy in Washington the previous November. The historian Srinath Raghavan points me to a revealing letter from his archival database, written on Valentine's Day 1962 by Mr. Nehru's sister, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, to Lord Mountbatten:

"You know bhai has been rather seriously ill... He has aged in a frightening manner. One can hardly hear him speak across the dinner table because his voice has almost disappeared, he walks with head and shoulders bent, he seems to have lost the keen interest in everything around him which was one of his marked characteristics... All Indian doctors are agreed that he must have a long rest - three to six months, in order to survive... There is irresponsible talk everywhere, even in the highest circles, and a whispering campaign is going on to the effect that the PM has lost his grip on the cabinet - that he cannot think clearly, cannot make decisions and so on."

Indira Gandhi would also find cause to be discreet about a disease, although at a time when she was still Nehru's daughter, and not political aspirant or Indian prime minister. In 1939, Ms. Gandhi checked into a plush sanatorium in Leysin, in Switzerland, to be treated for tuberculosis. At the time, writes Katherine Frank in Indira, consumptive patients "often had a leper complex. Tuberculosis was infectious and therefore stigmatized." Her doctor, Auguste Rollier, refused to use the word "tuberculosis," and,

"[T]o an extent, Indira and Nehru colluded in Rollier's deception, for they, too, never mentioned 'tuberculosis' in all the letters they wrote to each other... [T]o her father, she wrote only of her chronic low weight and increasing depression."

More examples abound. The Indian prime minister's office refused, in 2009, to grant a Right to Information request that sought to know how the former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri had died during a state visit to Tashkent in 1966. In 2009 too, news of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's heart surgery was released less than a day before he went under the knife.

The reluctance to admit frailty is perhaps a primal political instinct, linked closely to another such: the desire to retain power. But these Indian politicians seem to have ranked the strategic benefits of secrecy over the right of their constituencies to know how fit their leaders are.

When they do, they veer toward behaving like rulers who build cults of personality, seeming to worry that weakness - even of a temporary, physiological sort - will jeopardize their power and spark new bids for their position. "The talk is about succession and nothing else," Ms. Pandit wrote to Lord Mountbatten in 1962 - a fearsome observation for India's politicians, even today.

Then even that trickle dried up; the party released no official word on what she was being treated for, where she was being treated, or when precisely she would return. When presented with rumors - of cancer, of a visit to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, of an Indian-origin oncologist being mysteriously called away from holiday - the party replied with grim silence. (She's back now - or so we were told, in an equally laconic vein.)

In this, Sonia Gandhi appeared to be following in an established tradition, by which Indian political leaders guard news of their health as if it were a state secret. Not for them the publicly fought battles of Rudy Giuliani against his prostate cancer, of Dick Cheney against his troublesome heart, or of Hugo Chavez against his recent pelvic abscess. Even the example of Mahatma Gandhi - who let it all hang out, often greeting his ashram's residents with updates about his bowel movements - is an aberration in Indian politics. The health bulletins that Mr. Gandhi issued during his various imprisonments and protest fasts may have been tools of political leverage, but they were also ways to reach out to a population that loved him deeply.

Subsequent leaders have been reticent for strategic reasons. Mohammad Ali Jinnah had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in June 1946, but he kept it from public knowledge; thus, in those charged years, few knew that Mr. Jinnah had little time left to push for an independent Pakistan. He died in September 1948, a mere 13 months after the creation of Pakistan.

It was said of Jawaharlal Nehru that India's 1962 war against China - against the fraternal power in his ideal of Asianism - sickened him and hastened his demise. But even in photographs from just before the war - from September 1962, for instance, with the nuclear scientist Homi Bhabha - Mr. Nehru seems to look haggard and ill, very different from the fit, cheerful prime minister who had met Jackie and John F. Kennedy in Washington the previous November. The historian Srinath Raghavan points me to a revealing letter from his archival database, written on Valentine's Day 1962 by Mr. Nehru's sister, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, to Lord Mountbatten:

"You know bhai has been rather seriously ill... He has aged in a frightening manner. One can hardly hear him speak across the dinner table because his voice has almost disappeared, he walks with head and shoulders bent, he seems to have lost the keen interest in everything around him which was one of his marked characteristics... All Indian doctors are agreed that he must have a long rest - three to six months, in order to survive... There is irresponsible talk everywhere, even in the highest circles, and a whispering campaign is going on to the effect that the PM has lost his grip on the cabinet - that he cannot think clearly, cannot make decisions and so on."

Indira Gandhi would also find cause to be discreet about a disease, although at a time when she was still Nehru's daughter, and not political aspirant or Indian prime minister. In 1939, Ms. Gandhi checked into a plush sanatorium in Leysin, in Switzerland, to be treated for tuberculosis. At the time, writes Katherine Frank in Indira, consumptive patients "often had a leper complex. Tuberculosis was infectious and therefore stigmatized." Her doctor, Auguste Rollier, refused to use the word "tuberculosis," and,

"[T]o an extent, Indira and Nehru colluded in Rollier's deception, for they, too, never mentioned 'tuberculosis' in all the letters they wrote to each other... [T]o her father, she wrote only of her chronic low weight and increasing depression."

More examples abound. The Indian prime minister's office refused, in 2009, to grant a Right to Information request that sought to know how the former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri had died during a state visit to Tashkent in 1966. In 2009 too, news of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's heart surgery was released less than a day before he went under the knife.

The reluctance to admit frailty is perhaps a primal political instinct, linked closely to another such: the desire to retain power. But these Indian politicians seem to have ranked the strategic benefits of secrecy over the right of their constituencies to know how fit their leaders are.

When they do, they veer toward behaving like rulers who build cults of personality, seeming to worry that weakness - even of a temporary, physiological sort - will jeopardize their power and spark new bids for their position. "The talk is about succession and nothing else," Ms. Pandit wrote to Lord Mountbatten in 1962 - a fearsome observation for India's politicians, even today.

No comments:

Post a Comment